CASES

CASES

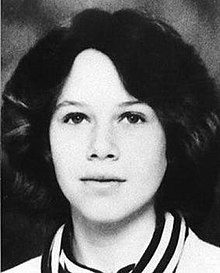

CASE: 424673-RS Beverly Potts

August 24, 1951, when a young, 10-year-old girl named Beverly Potts went off with a friend, Patricia Swing, to visit Halloran Park, in Cleveland, Ohio, in order to watch some performers at a lively summer festival. Swing had to return home at around 9PM, but Beverly decided to stay behind to watch the show to its end. However, she would not ever make it home that night and the following morning she was still nowhere to be seen. She had simply disappeared into thin air.

Thus would begin one of the largest scale searches in Cleveland history, as law enforcement launched an intensive search operation bolstered by thousands of concerned volunteers, who poured in to aide in the hunt for the missing child, scouring practically every inch of the city for any sign of her. In the meantime there were countless tips and leads, but none of these led anywhere, and in the end the child’s whereabouts remained frustratingly elusive. Despite pursuing every available lead and interviewing dozens of possible persons of interest, the police were never able to ever get any closer to finding out what had happened to Beverly, she remained missing, and no solid clues could be obtained.

Oddly, the only real clues began to come in decades later in the form of eerily strange letters that turned up. The first was in 1994, when a letter was discovered by accident in a renovated house, which claimed that the writer’s husband had brutally murdered Beverly and disposed of the body. Although this was seen as a groundbreaking potential clue at the time, it turned out to be a dead end when it was determined that the letter had likely been an attempt by the woman to get revenge on her husband for years of abuse by framing him for the crime. After this revelation, the letter of potential evidence.

Then, in 2000, the news publication The Plain Dealer received a series of odd and anonymous letters that served to stir up the case once again. The first letter simply stated that the writer had killed Beverly Potts after kidnapping and molesting her, and described how he had decided to confess because he was dying of an unspecified illness. Over the next year, three more such letters would arrive from the same individual, each giving further grim details into the kidnapping and murder, and they were seen as being a rather credible lead in the case at the time. Some intriguing promises were made in the exchange. The second letter promised that the writer had arranged upon his death to have sent a sealed brown envelope which would supposedly include even more details and proof of the admission in the form of a rare coin that Beverly was known to carry around with her.

Later, in the third letter, the author of the mysterious letters ended up offering to actually turn himself in. He claimed that he would appear in Halloran Park on the 50th anniversary of the mysterious vanishing, saying “Fifty years is long enough to live with what I’ve done,” yet on the anniversary he was a no-show, and merely sent one final letter. In this last letter, he merely stated that he had decided not to turn himself in after all, and gave the cryptic clue that he had checked himself into a nursing home. This would be the last letter from the mysterious sender, and no one would hear from him again.

As none of the letters were signed there is no way to know who they were sent by or how much veracity they have. They have been considered to be anything from the real deal to an elaborate and rather tasteless hoax. Nobody knows, and the disappearance of Beverly Potts has never been close to being solved, despite constant pleas for information, relentless following of new leads in the case, and increasingly hefty rewards offered. The mystery has been made into a book called Twilight of Innocence — The Disappearance of Beverly Potts, by historian James Badal, and was also the focus of the documentary Dusk and Shadow — The mystery of Beverly Potts. The mysterious vanishing has gone on to be a legendary case in Cleveland, regularly appearing in the news even to this day, and Beverly has earned the nickname “The Little Girl Clevelanders Can’t Forget.”